Poor Emilio! He seemed like such a confident student, but when he had to give a talk in front of the class, he ran to the bathroom and was sick. Emilio’s case might be extreme, […]

Prosody Practice: Talk Show Activity

Alice Savage, author of the forthcoming The Drama Book, has been doing plays with her students for a while now. But she wanted to know if the prosody practice her students have been doing with […]

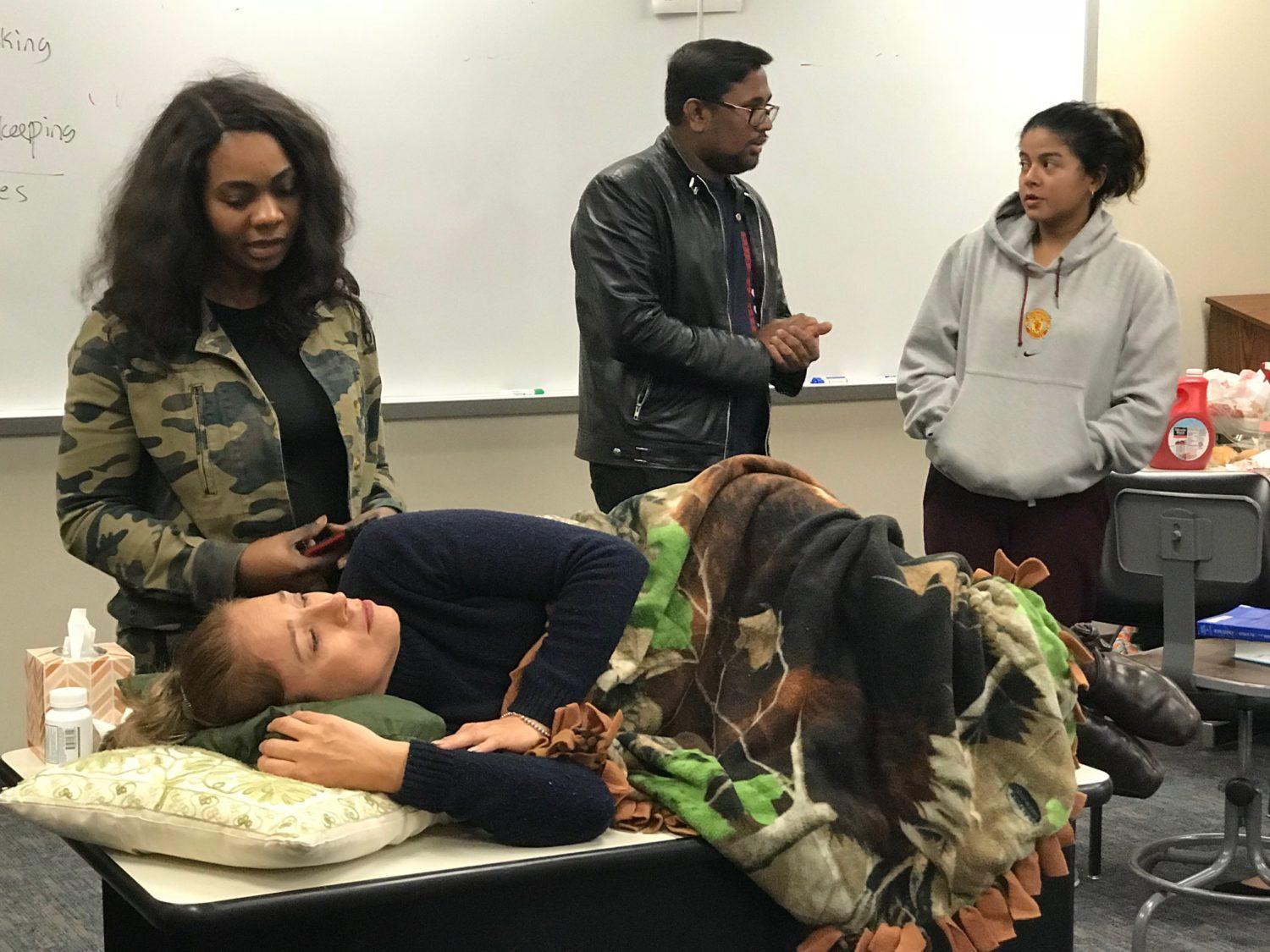

Improvised Role Plays of Real-World Conversations

Improvisation allows students to prepare for real world situations, but often in regular role plays, the conversation runs more smoothly than in real life. In the real world, people find themselves challenged by awkward situations. […]

Play on Feelings: Using Intonation to Express Emotions

Intonation is notoriously difficult for English learners, yet it is important, particularly in English, for sending emotional messages. The role of intonation in English is complicated but generally English speakers use intonation to express emotion, […]

Pragmatics is Everywhere

I got this amazing feedback from an educator about one of our drama books and how teaching pragmatics resonates with her students: I introduced the idea of using [Her Own Worst Enemy] in the classroom […]

Slides from TESOL 2019 Presentations

It was an honor to present at the 2019 TESOL Conference and spread the word about using drama and video in language learning. Our author, Taylor Sapp, also presented on using his story prompts to […]

How to Put on a Play in Class

The benefits of drama in the English classroom are surprising. Students learn and practice a variety of acting skills, using their bodies and voices to make meaning. When they put on a play, what to […]

Conversational Moves

So many speaking materials focus on micro-language: application of a grammatical form, pronunciation of a syllable, maybe memorization of a useful phrase. But students do not get much scaffolding for a macro-approach that integrates larger elements […]

Using Video to Teach Natural Conversation

Video is a powerful resource to teach natural conversation to students. Students can benefit from listening to conversations between fluent speakers. In particular, natural, fluent speech provides models of pronunciation and intonation, and how we […]

How to do a Play with ESL Students

Producing a play in class can be an amazing learning experience. Drama is more than just a way to cover a book or a fun treat! Plays are a powerful too for teaching speaking skills, […]